Several years

ago I pulled into a gas station to fill up my car. Those who know me also know

I have a penchant, some may say affliction, for vintage British sports cars.

The car in question was a British Racing Green Austin-Healey with a vanity

plate that read Kaladi. The particular station had an espresso cart operated by

a new roaster in town. Upon seeing the plate on the car the young man came out

and informed me that "they had better beans."

"How are

they better? I queried.

"They buy better beans," he responded.

"That's interesting," I replied,

"I'm the coffee buyer for Kaladi and I am very particular about coffee

quality so I would be interested in how your coffee is better."

"They

buy better beans," he said and walked off.

If there is

one thing for certain it’s that every coffee roaster only buys the very best beans.

Whether its a narrative of their intrepid globe spanning coffee buyer or some

statement of how selective their requirements are, it seems that every coffee

roaster would like you to believe that they have the sole purview over quality.

But how does one define quality in the coffee industry? It's a worthwhile

question, and one open to contention.

For the most

part, when a roaster claims they buy the best beans, they are referring to the

grade of coffee. There are a few

different ways in which coffee is graded. What they most have in common is that

the fewer number of defects, those things that would have an adverse effect on

the flavor, the higher the grade. Defects could be things like blackened beans,

or sour beans, insect infected beans, or diseased beans, moldy beans or

fermented beans, or simply things that are not beans at all, like sticks or

stones.

To aid in

this removal of defects, it is helpful if the beans share a similar size and

density. Bigger beans are equated to healthier beans: greater density in beans

is generally equated to higher elevation. When the beans are the same general

size and density they flow through the pulping and milling equipment more

effectively. Consistency is also necessary when using color sorting devices

that separate defective beans using spectronomy. Uniform bean size and density

was once more important to roasters as well to ensure a more uniform roast,

albeit newer technology in roasters has rendered this less important today.

There is a

confusing array of terms to designate a coffee's grade, there being no globally

recognized lexicon indicating grade. Some countries use names to designate

grade, like Supremo, Extra Fancy, Kohlinoor; others use various letter or

number designations, such as Grade 1, AA, SHB, SHG, etc. Additionally, these

grades may be different according to the import market: a AA grade may not be

the same for the US as for Europe. Generally speaking, though, the higher the grade,

the bigger, more uniform density the beans are with the fewest allowable

defects.

Grading is

done at the export mill, often just before export. As the coffee is bagged it

is marked with an identifying number indicating its lot. A lot is a set number

of bags that will fit into a shipping container, usually 250, assuming that the

bags are around 70 kilos or 150 or so pounds. Of course, different countries

will have different size bags as well so this will affect the number of bags in

a lot. Lot sizes can also be smaller in cases

where a buyer has specified a particular preparation or segregation of a

coffee. But it is this number assigned that is ultimately important as this

will theoretically follow the coffee to its destination. A coffee bag will have

a total of three numbers for identification; the first designates its country

of origin, the second the export mill that prepared the coffee, the last the

individual lot.

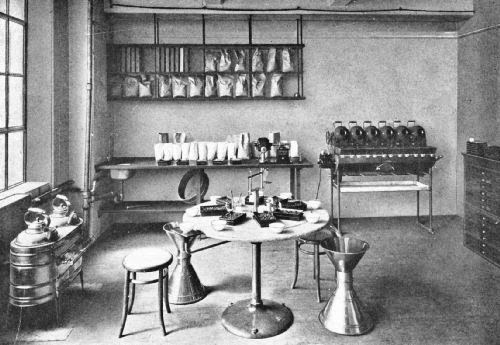

Along the way

the coffee will be evaluated by cuppers. Historically this has been the purview

of the exporting firm and the importing firm. In practice today, this model is

more variegated, but suffice it to say that these cuppers are operating within

the "trading" of coffee and so are often called trade cuppers. Trade

cupping concerns itself largely with identifying faults and defects in flavor

that grading misses. The role of the trade cupper is to act as a gatekeeper for

exporter or importer. The last thing these firms want to have happen is for a

lot of coffee to be rejected by the buyer because of a fault in the flavor. Best

to catch these things before the coffee has left the port. Trade cupping

concerns itself with identifying faults such as ferment, mold, past crop, taints

from improper preparation or storage, anything that would mar the coffee's

flavor and risk rejection by the end buyer, whether that is an importing firm

or a roasting firm.

In order to

assess coffee for defects the coffee is roasted very light so that certain

taints, especially ferment and mold, are more pronounced. At a certain point in

roasting, the roast itself can make it more difficult to suss out these faults

but they are still there. The fact is, if you are cupping a number of coffees

on a cupping table there's no time for subtlety. You want things to slap you in

the face. You are not looking for the finer points of the coffee's character,

only making sure that you and your firm are protected from a rejected shipment.

Trade cupping is not necessarily about determining quality as it is about

ensuring that the coffee is fit for export. That being said, experienced

professional trade cuppers are astute identifiers of real quality. They can

recognize virtually all aspects to a coffee's growing and preparation in just 5

cups. Some of these cuppers work for famous estates and exporting mills

crafting signature flavor profiles from their production area or estate.

The concept

of flavor quality, however, is a far more complicated concept to come to an

understanding on. One could erroneously

believe that there is some sort of objective standard we could agree on, but

here we move away from taste faults into the realm of taste preferences. For

the better part of the last century coffee was experienced as a blend. These

blend profiles, at least at first, were a roaster's signature, their trademark.

Its helpful to remember that Maxwell House Coffee gets its name from the

Maxwell House Hotel, who awarded the contract (and name) based on winning a

tasting competition. Hills Bros, too, was well regarded for the

"Arabian" blend featuring Mocca and Java coffees.

Over the

years, though, these brands began competing on price and this put pressure on

the coffee buyers to reformulate the blends for price. Before this change in

priorities, coffee buyers had specific taste requirements in order to shape the

blend. Not only would the coffee need to be clean and defect free, it needed to

fulfill a particular taste profile within the blend. This devolved into

hopelessly muddled blends, largely indistinguishable from one another where

coffee buyers sought the cheapest possible coffee that offended the fewest

number of people. With blends consisting of a dozen or more individual

components, it is fairly simple to replace one with another and the consumer

would be unable to notice any change.

Along with cheapening the beans themselves, there was a push to reduce

weight loss during roasting with lighter and lighter roasts, becoming known as

"Continental" or simply "American" roasts.

By the

1960's, the lion’s share of the U.S. coffee market was dominated by

just a few roasting firms: Smuckers, who has Folgers; Kraft with Maxwell House;

Nestle and Sara Lee. Most coffee sales were through the grocery isle, and

couponing dictated who garnered the most sales. As the flavor quality declined

in these brands the number of new customers to coffee waned. And for those who

continued drinking this swill, the amount of sweeteners and "creaming

agents" increased. The National Coffee Association conducted a yearly

winter drinking survey and consumption was decreasing every year well into the

1980s.

But it wasn't

only about price in blending coffee beans, there were a number of smaller,

regional roasters that still relied on flavor quality to lure customers. Some

of them date back to the early days of coffee in America like Gillies Coffee of New

York. Others were a direct response to the ever worsening quality in commercial

coffee, a return to quality, such as Peet's Coffee in California.

These roasters distinguished themselves from the commercial canned

coffee by retaining the darker, European style of roasts and sourcing out

quality beans that could stand up to such roasts. Ever so slowly, a new breed

of roaster began to grow in America,

what now is referred snarkily as the “second wave.”

Roasters such

as this relied on specific flavors of coffee that represented their brand.

Whether packaged as a single origin or a signature blend, coffees were chosen

for their flavor profile. A coffee buyer for these firms would seek out coffees

based on these profiles. Some were the "classics" of coffee: Sumatra

and Kenya,

for example. Others were less well known here in the states, but came from

respected estates that had for years prepared special coffees for the European

market. These coffees were more carefully sorted and processed, for more

exacting coffee buyers. Sometimes you will still see a coffee identified as

"European Prep."

In any case,

a coffee buyer for these firms expected high quality beans from their sources

and rather than trade cupping the coffees for defects, they instead cupped for

profile. Rather than roasting the samples very light, the samples would be

roasted closer to production temperatures to tease out the potentials of the

coffee. In this way a coffee buyer would be able to see if the coffee would fit

with the profiles they wished to promote. A coffee buyer here would still be

expected to recognize taste faults, but their primary objective was looking for

favorable flavor attributes whether that was part of a blend or a stand alone

coffee.

Depending on

the size of the firm, such cupping would include samples, from production as

well to ensure the roasts were coming out right. While this type of cupping

differs in style and intent from trade cupping, it was never really identified

separately as such. One could call it profile cupping or production cupping,

but rarely would someone differentiate it, referring to both simply as

cupping. It was, generally speaking, new

territory anyway, and there existed a lack of common language for this type of cupping.

This would

become problematic as time progressed. Without a lexicon to describe quality,

it made it difficult to define quality. The materials at the time focused

around faults and defects, barely mentioning favorable taste attributes beyond

something like, “clean,” “balanced,” “smooth”

and so forth. So, if you wanted to set out to buy the best coffee you would be

hard pressed to describe exactly what that meant. So we can forgive the young

man in the beginning of this story for not being capable of defining what he

meant by having better beans. The problem was systemic to the trade.

In 1982 many

of these roasters gathered together to create a "common forum" to

promote quality coffee. The idea was to unite those in the coffee trade to a

common purpose: to serve as a sounding board and educate the public; and to generally

be a source of support in a world of coffee mediocrity. This group became known

as the Specialty Coffee Association of America and is today the world's largest

coffee association. Over the years, the SCAA has attempted a number of

initiatives designed to promote coffee quality, and naturally one of these

would be to develop a standard of what "specialty" coffee is.

Much of this

early work consisted of developing guides for common usage. Ted Lingles's 1985

handbook, The Basics of Cupping Coffee,

now in its fourth edition, was one such handbook. In it, he outlines his

objective stating that it was "written as a sales and marketing tool(,) to

promote specialty coffee, adding further that it was "designed to initiate

discussion on the most appropriate and descriptive terminology" and

"does not presume to be the definitive text."

In addition

to producing material, the SCAA began hosting seminars on cupping specialty

coffee during its annual exhibition and trade show. In the past, learning to

cup coffee was sort of an arcane endeavor, usually reserved for those in the

business. Traders would learn from other traders, roasters would learn from

roasters. Coffee buyers were often somewhere in between. On the one hand, they

needed to be conversant with traders to access quality coffees, but on the

other, needed to understand what worked from a production standpoint. A good

coffee buyer would need to learn how to navigate these two perspectives. I have

known too many roasting firms where there existed an acrimonious divide between

the coffee buyer and roaster on what constitutes good coffee. Usually this

resulted from a coffee buyer who spent a fair amount of time "in the

field," who becave acclimated to trade cupping and lost the perspective of customer preferences and

expectations.

So,

establishing a common vocabulary for coffee quality would be a good thing, and

training would seem to be the perfect endeavor for the SCAA since its mission

is to promote specialty coffee. To this end, it has adopted a program called

the Q-Grader Certification that sets forward a systematic framework for

evaluating and describing specialty coffee. Using the cupping form originally

set out in the Coffee Cupper's Handbook it establishes a training program to

certify participants to identify and rate specialty grade coffee. The Q

certification is as good as any metric to create a normative vocabulary for

assessing quality.

Sadly though,

the SCAA has made the same mistake in perspective.

How this mistake in perspective played out is the subject of

part two.